Opening the Door to the Dhamma

Respect in Buddhist Thought And Practice

By Thanissaro Bhikkhu

If you're born into an Asian Buddhist family, the first thing your parents will

teach you about Buddhism is not a philosophical tenet but a gesture of respect:

how to place your hands in añjali, palm-to-palm over your heart, when you

encounter a Buddha image, a monk, or a nun. Obviously, the gesture will be mechanical

at first. Over time, though, you'll learn the attitude of respect that goes with

it. If you're quick to pick it up, your parents will consider it a sign of intelligence,

for respect is basic to any ability to learn.

As you get older, they may teach you the symbolism of the gesture: that your hands

form a lotus bud, representing your heart, which you are presenting to the object

of your respect in hopes of being trained in how to become wise. Ultimately, as

you grow more familiar with the fruits of Buddhist practice, your parents hope

that your respect will turn into reverence and veneration. In this way, they give

a quick answer to the old Western question of which side of Buddhism -- the philosophy

or the religion -- comes first. In their eyes, the religious attitude of respect

is needed for any philosophical understanding to grow. And as far as they're concerned,

there's no conflict between the two. In fact, they're mutually reinforcing.

This stands in marked contrast to the typical Western attitude, which sees an

essential discrepancy between Buddhism's religious and philosophical sides. The

philosophy seems so rational, placing such a high value on self-reliance. The

insight at the heart of the Buddha's Awakening was so abstract -- a principle

of causality. There seems no inherent reason for a philosophy with such an abstract

beginning to have produced a devotionalism intense enough to rival anything found

in the theistic religions.

Yet if we look at what the Pali Canon has to say about devotionalism -- the attitude

it expresses with the cluster of words, respect, deference, reverence, homage,

and veneration -- we learn not only that its theory of respect is rooted in the

central insight of the Buddha's Awakening -- the causal principle called this/that

conditionality (idappaccayata) -- but also that respect is required to learn and

master this causal principle in the first place.

On the surface it may seem strange to relate a theory of causality to the issue

of respect, but the two are intimately entwined. Respect is the attitude you develop

toward the things that matter in life. Theories of causality tell you if anything

really matters, and if so, what matters and how. For instance, take the what:

If you believe that a supreme being will grant you happiness, you'll naturally

show respect and reverence for that being. If you assume happiness to be entirely

self-willed, your greatest respect will be reserved for your own willfulness.

As for the how: If you view true happiness as totally impossible, totally pre-determined,

or totally random, there's no need for respect, for it will make no difference

in the outcome of your life. But if you see true happiness as possible, and its

causes as precarious, contingent, and dependent on your attitude, you'll naturally

show them the care and respect needed to keep them healthy and strong.

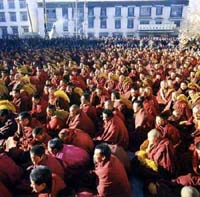

This is reflected in the way the Canon treats the issue of respect. It depicts

in great detail the varied ways in which lay people of the Buddha's time showed

respect to the Buddha and the monastic Sangha, and the more standardized ways

in which the members of the Sangha showed respect to the Buddha and to one another.

Especially interesting is the protocol of respect surrounding the teaching of

the Dhamma. Buddhist monks and nuns are forbidden from teaching the Dhamma to

anyone who shows disrespect, and the Buddha himself is said to have refused to

teach his first sermon to the five brethren until they stopped treating him as

a mere equal.

This protocol, of course, may have simply been a cultural accident, something

picked up willy-nilly from the society of the Buddha's time, but there are passages

in the Canon suggesting otherwise. Buddhism was one of the samana (contemplative)

movements in ancient India, which claimed to follow truths of nature rather than

mainstream cultural norms. These movements were very free in choosing what to

adopt from prevailing customs. Buddhist descriptions of other samana movements

often criticized them for being disrespectful not only to outsiders but also among

themselves. Students are shown being disrespectful to their teachers, their group

meetings raucous, noisy, and out of control. All of this is then contrasted with

the way Buddhists conduct their meetings in mutual courtesy and respect. This

suggests that the Buddhists were free to reject the common customs of respect

but made a conscious choice not to.

This choice is based on their insight that respect is a prerequisite for learning.

You find it easier to learn from someone you respect than from someone you don't.

Respect is what opens your mind and loosens your preconceived opinions to make

room for new knowledge and skills. At the same time, a person with a valuable

teaching to offer will feel more inclined to teach it to someone who shows respect

than to someone who doesn't.

However, the type of learning the Buddha emphasizes is not simply the acquisition

of information. It's a skill that allows you to master other skills leading to

total release from suffering and stress. And this is where the issue of respect

connects with causality, for the Buddhist theory of causality centers on the question

of how it's possible to learn a skill.

As cybernetics theory shows, learning is possible only where there is feedback;

learning a skill requires the further ability to monitor feedback and choose how

to use it to modify behavior. The Buddha's discoveries in causality explain the

how and the what that allow for these factors. The how he expressed as a causal

formula; the what, as an analysis of action: the factors that shape it, together

with the range of results it can give.

The causal formula, simply put, states that each moment is composed of three things:

results from past actions, present actions, and the immediate results of present

actions. Although this principle seems simple, its consequences are very complex.

Every act you perform has repercussions in the present moment that also reverberate

into the future. Depending on the intensity of the act, those reverberations can

last for a very short or a very long time. Thus every conditioned experience is

shaped by the combined effects of past actions coming from a wide range over time,

together with the effects of present acts.

Causality over time places certain limitations on each moment. The present is

not a clean slate, for it's partially shaped by influences from the past. Immediate

causality in the present, however, makes room for free will. Not everything is

determined by the past. At any moment, you can insert new input into the process

and nudge your life in a new direction. Still, there is not so much room for free

will that causality becomes arbitrary. Each specific this in this/that conditionality

-- whether acting over time or in the immediate present -- is always associated

with a specific that. Events follow predictable patterns that can be mastered.

The what that keeps this process in motion is the factor that allows for feedback

and the monitoring of feedback. The primary element in that what is intention,

which the Buddha identified as the essence of action, or kamma. Intention, in

turn, is shaped by acts of attention, which ask questions about perceptions and

create views from those questions. Because you can attend to the results of your

intentions, there is a feedback loop in your mind that allows you to learn. Because

attention can ask questions, it can monitor that feedback to determine how it

can best be put to use. And because your intentions -- guided by views and offering

new input into the present -- can then reshape your experience, your ability to

learn can make a difference: you can change your behavior and reap the results

of your improved skills in terms of greater and greater happiness.

How far can that happiness go? In the course of his Awakening, the Buddha discovered

that the pursuit of skillfulness can ultimately lead totally beyond the realm

of rebirth. From this discovery he identified four types of kamma: the first three

giving pleasant, painful, or mixed results in the round of rebirth, and the fourth

leading beyond all kamma to the end of the round of rebirth. In other words, the

principle of causality works so that actions can either continue the round of

rebirth or bring it to an end. Because even the highest pleasure within the round

is inconstant and undependable, he taught that the most worthy course of action

is the fourth kind of kamma -- the type that led to his Awakening -- to put an

end to kamma once and for all.

The skill embodied in this form of kamma comes from coordinating the factors of

attention and intention so that they lead first to pleasant results within the

round of rebirth, and then -- on the transcendent level -- to total release from

suffering and stress. This, in turn, requires certain attitudes toward the principle

of causality operating in human life. And here the quality of respect becomes

essential, for without the proper respect for three things -- yourself, the principle

of causality operating in your life, and other people's insights into that principle

-- you won't be able to muster the resolve needed to master that principle and

to see how far your potential for skillfulness can go.

Respect for yourself, in the context of this/that conditionality, means two things:

1) Because the fourth kind of kamma is possible, you can respect your desire for

unconditional happiness, and don't have to regard it as an unrealistic ideal.

2) Because of the importance of intention and attention in shaping your experience,

you can respect your ability to develop the skills needed to understand and master

causal reality to the point of attaining true happiness.

But respect for yourself goes even further than that. Not only can you respect

your desire for true happiness and your ability to attain it, you have to respect

these things if you don't want to fall under the sway of the many religious and

secular forces within society and yourself that would pull you in other directions.

Although most religious cultures assume true happiness to be possible, they don't

see human skillfulness as capable of bringing it about. By and large, they place

their hopes for happiness in higher powers. As for secular cultures, they don't

believe that unconditional happiness is possible at all. They teach us to strive

for happiness dependent on conditions, and to turn a blind eye to the limitations

inherent in any happiness coming from money, power, relationships, possessions,

or a sentimental sense of community. They often scoff at higher values and smile

when religious idols fall or religious aspirants show feet of clay.

These secular attitudes foster our own unskillful qualities, our desire to take

whatever pleasures come easily, and our impatience with anyone who would tell

us that we are capable of better and more. But both the secular and the common

religious attitudes teach us to underestimate the powers of our own skillful mind

states. Qualities like mindfulness, concentration, and discernment, when they

first arise in the mind, seem unremarkable -- small and tender, like maple seedlings

growing in the midst of weeds. If we don't watch for them or accord them any special

respect, the weeds will strangle them or we ourselves will tread them underfoot.

As a result, we'll never get to know how much shade they can provide.

If, however, we develop strong respect for our own ability to attain true happiness,

two important moral qualities will take charge of our minds and watch out for

our good qualities: concern for the suffering we'll experience if we don't try

our best to develop skillfulness, and shame at the thought of aiming lower than

at the highest possible happiness. Shame may seem a strange adjunct to self-respect,

but when both are healthy they go together. You need self-respect to recognize

when a course of action is beneath you, and that you would be ashamed to follow

it. You need to feel shame for your mistakes in order to keep your self-respect

from turning into stubborn pride.

This is where the second aspect of respect -- respect for the principle of causality

-- comes in. This/that conditionality is not a free-form process. Each unskillful

this is connected to an unpleasant that. You can't twist the connection to lead

to pleasant results, or use your own preferences to design a customized path to

release from causal experience. Self-respect thus has to accommodate a respect

for the way causes and effects actually behave. Traditionally, this respect is

expressed in terms of the quality the Buddha stressed in his very last words:

heedfulness. To be heedful means having a strong sense that if you're careless

in your intentions, you'll suffer for it. If you truly love yourself, you have

to pay close attention to the way reality really works, and act accordingly. Not

everything you think or feel is worthy of respect. Even the Buddha himself didn't

design Buddhism or the principle of this/that conditionality. He discovered them.

Instead of viewing reality in line with his preferences, he reordered his preferences

to make the most of what he learned by watching -- with scrupulous care and honesty

-- his actions and their actual effects.

This point is reflected in his discourse to the Kalamas. Although this discourse

is often cited as the Buddha's carte blanche for following your own sense of right

and wrong, it actually says something very different: Don't simply follow traditions,

but don't simply follow your own preferences, either. If you see, through watching

your own actions and their results, that following a certain mental state leads

to harm and suffering, you should abandon it and resolve never to follow it again.

This is a very rigorous standard, which requires putting the Dhamma ahead of your

own preconceived preferences. And it requires that you be very heedful of any

tendency to reverse that priority and put your preferences first.

In other words, you can't simply indulge in the pleasure or resist the pain coming

from your own actions. You have to learn from both pleasure and pain, to show

them respect as events in a causal chain, to see what they have to teach you.

This is why the Buddha called dukkha -- pain, stress, and suffering -- a noble

truth; and why he termed the pleasure arising from the concentrated mind a noble

truth as well. These aspects of immediate experience contain lessons that can

take the mind to the noble attainments.

The discourse to the Kalamas, however, does not stop with immediate experience.

It goes further and states that, when observing the processes of cause and effect

in your actions, you should also confirm your observations with the teachings

of the wise. This third aspect of respect -- respect for the insights of others

-- is also based on the pattern of this/that conditionality. Because causes are

sometimes separated from their effects by great expanses of time, it's easy to

lose sight of some important connections. At the same time, the mental quality

that acts as your chief obstacle to discernment -- delusion -- is the one you

have the hardest time detecting in yourself. When you're deluded, you don't know

you're deluded. So the wise approach is to show respect to the insights of others,

in the event that their insights may help you see through your own ignorance.

After all, intention and attention are immediately present to their awareness

as well. Their insights may be just what you need to cut through the obstacles

you've created for yourself through your own acts of ignorance.

The Buddhist teachings on respect for other people point in two directions. The

first direction is the obvious one: respect for those who are further along the

path than you. As the Buddha once said, friendship with admirable people is the

whole of the holy life, for their words and examples will help get you on the

path to release. This doesn't mean that you necessarily have to obey their teachings

or to accept them unthinkingly. You simply owe it to yourself to give them a respectful

hearing and their teachings an honest try. Even -- especially -- when their advice

is unpleasant, you should treat it with respect. As Dhammapada 76 states,

Regard him as one who

points out

treasure,

the wise one who

seeing your faults

rebukes you.

Stay with this sort of sage.

For the one who stays

with a sage of this sort,

things get better,

not worse.

At the same time, when you show respect for those who have mastered the path,

you're also showing respect for qualities you want to develop in yourself. And

when such people see that you respect the good qualities both in them and in yourself,

they'll feel more inclined to share their wisdom with you, and more careful about

sharing only their best. This is why the Buddhist tradition places such an emphasis

on not only feeling respect but also showing it. If you can't force yourself to

show respect to others in ways they'll recognize, there's an element of resistance

in your mind. They, in turn, will have doubts about your willingness to learn.

This is why the monastic discipline places so much emphasis on the etiquette of

respect to be shown to teachers and senior monastics.

The teachings on respect, however, go in another direction as well. Buddhist monks

and nuns are not allowed to show disrespect for anyone who criticizes them, regardless

of whether or not that person is awakened or the criticism well-founded. Critics

of this sort may not deserve the level of respect due to teachers, but they do

deserve common courtesy. This is because, as stated above, the patterns of cause

and effect are present to everyone's awareness, and even un-awakened people may

have observed valuable bits and pieces of the truth. If you open yourself to criticism,

you may get to hear some worthwhile insights that a wall of disrespect would have

repelled. Buddhist literature -- from the earliest days up to the present -- abounds

with stories of people who gained Awakening after hearing a chance word or a phrase

of a song from an unlikely source. A person with the proper attitude of respect

can learn from anything -- and the ability to put anything to a good use is the

mark of true discernment.

Perhaps the most delicate skill with regard to respect is learning how to balance

all three aspects of respect: for yourself, for the truth of causality, and for

the insight of others. This balance, of course, is essential to any skill. If

you want to become a potter, for example, you have to learn not only from your

teacher, but also from your own actions and powers of observation, and from the

clay itself. Then you have to weigh all of these factors together to achieve a

mastery of your own. If, in your pursuit of the Buddhist path, your self-respect

outweighs your respect for the truth of causality or the insights of others, you'll

find it difficult to take criticism or to laugh at your own foolishness. This

will make it impossible for you to learn. If, on the other hand, your respect

for your teachers outweighs your self-respect or your respect for the truth, you

open yourself to charlatans and close yourself to the truth that the Canon says

"is to be seen by the wise for themselves."

The parallels between the role of respect in Buddhist practice and in manual skills

explains why many Buddhist teachers require their students to master a manual

skill as a prerequisite or a part of their meditation. A person with no manual

skills will have little intuitive understanding of how to balance respect. What

sets the Buddha's apart from other skills, though, is the level of total freedom

it produces. And the difference between that freedom and its alternative -- endless

rounds of suffering through birth after birth, death after death -- is so extreme

that we can easily understand why people who have given themselves to the pursuit

of that freedom show it a level of respect and veneration that's also extreme.

Even more understandable is the absolute level of respect and veneration for that

freedom shown by those who have attained it. They bow down to all their inner

and outer teachers with the sincerest, most heart-felt gratitude. To see them

bow down in this way is an inspiring sight.

So when Buddhist parents teach their children to show respect for the Buddha,

Dhamma, and Sangha, they aren't teaching them a habit that will later have to

be unlearned. Of course, the child will need to learn how best to understand and

make use of that respect, but at least the parents have helped open the door for

the child to learn from its own powers of observation, to learn from the truth,

and to learn from the insights of others. And when that door -- when the mind

-- is opened to what truly deserves respect, all things noble and good can come

in.